The new status symbol

A+

A-

The new status symbol: it’s not what you spend – it’s how hard you work

Ben Tarnoff in San Francisco

The Guardian | Monday 24 April 2017 07.00 BST Last modified on Monday 24 April 2017

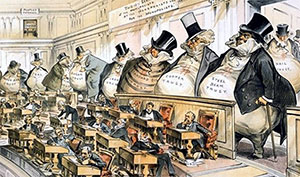

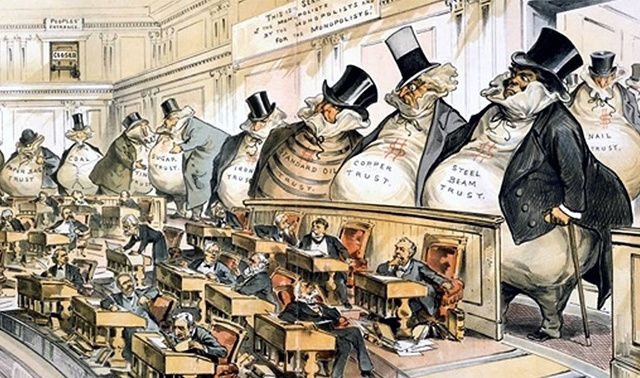

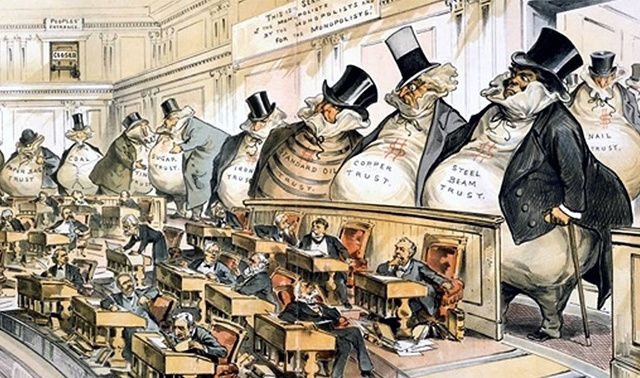

Almost 120 years ago, during the first Gilded Age, sociologist Thorstein Veblen coined the term “conspicuous consumption”. He used it to refer to rich people flaunting their wealth through wasteful spending. Why buy a thousand-dollar suit when a hundred-dollar one serves the same function? The answer, Veblen said, was power. The rich asserted their dominance by showing how much money they could burn on things they didn’t need.

While radical at the time, Veblen’s observation seems obvious now. In the intervening decades, conspicuous consumption has become deeply embedded in the texture of American capitalism. Our new Gilded Age is even more Veblenian than the last. Today’s captains of industry publicize their social position with private islands and superyachts while the president of the United States covers nearly everything he owns in gold.

But the acquisition of insanely expensive commodities isn’t the only way that modern elites project power. More recently, another form of status display has emerged. In the new Gilded Age, identifying oneself as a member of the ruling class doesn’t just require conspicuous consumption. It requires conspicuous production.

If conspicuous consumption involves the worship of luxury, conspicuous production involves the worship of labor. It isn’t about how much you spend. It’s about how hard you work.

Nowhere is the cult of conspicuous production more visible than among America’s CEOs. Today’s top executives are devoted work-worshippers, nearly to the point of perversity. Apple CEO Tim Cook told Timethat he begins his day at 3.45am. General Electric CEO Jeff Immelt told Fortunethat he has worked 100-hour workweeks for 24 years. Not to be outdone, Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer told Bloomberg Newsthat she used to work 130-hour workweeks. And so on.

It goes without saying that these individuals aren’t working out of necessity. The vast majority of Americans work because their survival depends on a wage. By contrast, Mayer, Immelt and Cook could retire tomorrow and still live very comfortably for the rest of their lives, with plenty left over to pass on to the next generation – their collective net worth is almost $1.5bn.

But conspicuous production isn’t about meeting one’s material needs. It’s about the public display of productivity as a symbol of class power. In an era of extreme inequality, elites need to demonstrate to themselves and others that they deserve to own orders of magnitude more wealth than everyone else. Cook is approximately 500,000% richer than the average American – but he wakes up at 3.45 in the morning. This is the hallmark of conspicuous production: it justifies the existence of an imperial class by showcasing their superhuman levels of industry.

The irony is that grueling workweeks aren’t exclusively an elite phenomenon. Far from it. Many less fortunate Americans perform similar feats of productivity, although they have fewer incentives and opportunities to advertise it. A recent study by the Economic Policy Institute found that Americans workers work significantly more hours than they did a few decades ago – especially women, black people and the poor. A black woman in the bottom fifth of earners worked 349 more hours in 2015 than she would have in 1979. The reason is simple: wages have barely budged since the 1970s, which means today’s workers have to work harder to make ends meet.

Compare the woman working long hours for minimum wage with the woman working the same hours for $30m a year. One is trying to avoid hunger and homelessness; the other is broadcasting her power and prestige. The labor of the latter isn’t necessary in the normal sense – but neither is a ten-thousand-dollar handbag. If conspicuous consumption celebrates gratuitous spending, conspicuous production celebrates gratuitous working. Both convey dominance by making a spectacle of excess.

In the first Gilded Age, excess looked like a woman in pearls alongside a woman in rags. In the second Gilded Age, it looks like a woman who works hundred-hour workweeks but doesn’t need the money, alongside a woman who works just as hard but can barely keep a roof over her head.

Yet conspicuous production takes many forms. Even people who can’t afford to retire tomorrow can still engage in some version of it and enjoy a portion of the elite status that it confers. Veblen’s most provocative argument was that the wastefulness of the rich inspired admiration, not anger. Other classes tried to emulate it as best they could: middle-class people couldn’t live like a railroad baron, but they could indulge in little luxuries to bid up their social standing. The same rule applies to conspicuous production. Most Americans will never attain the decadent heights of CEO-style hyperwork, but they can still make a fetish of productivity.

One way is to turn your leisure into labor by “working on yourself”. The most obvious example is exercise, which has acquired a compulsive character among members of the urban professional class. The neighborhoods where they’re likely to live are littered with boutique fitness studios such as SoulCycle and luxury gyms such as Equinox. These are places where the labor of self-improvement and self-purification continue long after the labor required to pay one’s bills ends. And they exist alongside a complementary ecosystem of juice bars and organic food stores, where one obtains the proper fuel to power the production of the self.

The stated reason for all this is “health”. But the amount of time that many better-off Americans spend exercising far exceeds what is required to be healthy. That’s because the intricate demands of today’s fitness and nutritional regimens aren’t ultimately about wellbeing. They’re designed to express class power. In the second Gilded Age, you can typically estimate a person’s tax bracket by their physique – class is literally inscribed on the body. Richer bodies aren’t just thinner but precisely muscled in all sorts of ways. They reflect an enormous and, strictly speaking, unnecessary expenditure of effort. They embody work in excess of need, signaling wealth through wastefulness and justifying one’s possession of it through the performance of personal virtue.

But you don’t have to be a CEO or an affluent professional to partake in conspicuous production. Technology has made it possible for everyone to see everything as an opportunity for productivity. You can measure your sleep, sex and steps with a Fitbit, your attractiveness with Tinder, your wittiness with Twitter, your popularity with Facebook. You can transform your personality into a dashboard of data streams that can be monitored, analyzed and optimized with the precision of an industrial process. You can turn your life into a factory – and not just metaphorically. In producing yourself, you produce economic value for others. The hours you spend on these platforms may be unwaged, but they generate real revenue for the companies that own them.

This is the genius of conspicuous production. It not only promotes a culture of overwork, it makes our dwindling amount of leisure time economically productive. There is no escape: either we’re working for the company or we’re working on ourselves, but we’re always working. “Eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours of what we will” was the anthem of the workers who first demanded the eight-hour-day more than a century ago.Those distinctions don’t make sense any more. Even our sleep is factored into our productivity score – the entrepreneur of the self never gets to clock out.

Today, the old slogan of the labor movement sounds like utopian science fiction. Imagine a society that claimed so little of our labor. Imagine a world where the poor didn’t have to work so hard to exist, and the rich didn’t have to work so hard to appear worthy of their wealth, because rich and poor didn’t exist.

© 2017 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

26-02-2019